Portland set a new record for the city’s longest heat wave last week: we experienced seven consecutive days with recorded temperatures at or above 95° Fahrenheit from Monday, July 25 to Sunday, July 31. The State of Oregon is currently reporting at least 15 related deaths, with at least seven deaths in Multnomah County alone. That number is expected to increase as medical examiners finish their investigations.

I’m confident elected officials are patting themselves on the back this week for their responses to the heat wave. Only seven dead? That’s a fraction of the 69+ deaths in Multnomah County attributed to the 2021 heat dome! All the air conditioners distributed, new work safety guidelines written, and emergency text messages paid off!

But each of those deaths is a failure. We’ll hear more about each death in the coming weeks. There will be reports on underlying conditions and audits about program effectiveness. There will be condolences, and promises to do better, and statements about how programs are going to increase their efforts to save people in the future.

Each of those deaths will remain a failure. Government failed each of those people in its most basic obligation. But each of us who live in and around Portland failed those people too. We failed them because we don’t have the ability or the will to hold elected leaders accountable.

The struggle to respond to heat waves

Government-led emergency response focuses on repairing property damage. There’s an entire system to deploy money and rebuilding supplies throughout the U.S. As we’ve seen with the on-going COVID 19 pandemic and the spread of monkeypox, that system isn’t equipped to keep people alive and improve their health after a mass-disabling event. And while those systems may help people who experience a tornado or a hurricane, they do far less for people caught in a long-lasting emergency.

Heat wave responses are even worse. Heat waves are the deadliest natural disasters. There’s little of the urgency we see in responses to earthquakes or wildfires or even COVID-19 prior to vaccines becoming available.

Most decision makers can sit in air-conditioned offices while planning responses. Most people who engage with government — people who vote, call elected officials, etc. — have the resources to find somewhere cool to go. Heck, depending on the level of resources someone has access to, they can just ride out a heat wave here by taking a vacation elsewhere. That’s what Mayor Ted Wheeler did last week. Everyone else, though, suffers.

It’s difficult to imagine effective emergency response for heat waves, but we can recognize the flaws in the current approach and make improvements. One of the biggest changes we need to make is how we consider an emergency response successful. Personally, I would consider heat wave responses successful if everyone survives that heat wave. Everyone who is alive at the beginning of an emergency should be alive at the end of the same emergency. That’s not how governments assess their responses; they see a surprisingly large number of deaths as acceptable losses. After all, if any level of government wanted to keep more people alive, we’d have some sort of mask mandate in place right now.

But preservation of life is relatively easy during heat waves. In most cases, people can survive if they have access to cooling spaces and they aren’t expected to work in the heat.

Air conditioner distribution can’t be the only response

After the 2021 heat dome, local governments focused on a few responses:

- The Oregon State Occupational Safety and Health Division created new permanent rules on work safety during heat waves

- Multiple levels of government launched efforts to provide more air conditioners to Oregon residents

- CAPA Strategies convened Heat Week with the City of Portland and surrounding counties to commemorate the people who died during the 2021 heat dome and to discuss climate change responses.

Heat Week’s activities included a panel on climate and mental health, a Pedalpalooza ride, and a heat first aid training. It’s tough to say how effective each of these events were. They may have mostly reached people who are already following heat wave and climate change news.

We can assess the new standards for worker safety though, because we saw how easily employers ignore such regulations last week. The oversight system is minimal: workers can report problems, but OSHA can take days to even respond to a complaint, let alone penalize an employer. During a heat wave, waiting days to respond can make an investigation a question of a worker’s death. A coalition of Oregon business groups are also suing to force the state to rollback the new rules.

The various efforts to distribute air conditioners to Portland residents are the most successful strategy local governments have pursued — despite substantial struggles in the process and concerns that air conditioners aren’t an effective response. Why air conditioners? The majority of the people who died during the 2021 heat dome lacked cooling units. As of 2020, an estimated 76 percent of Oregon residents have some sort of air conditioning unit in their homes.

The city’s partners had installed only 64 cooling units, out of the 3,000 units the city promised to have installed this summer, as of the beginning of June. The City of Portland expects to install a total of 15,000 cooling units by the end of 2026. Multnomah County provides air conditioners to clients of the county’s Aging, Disability and Veterans Services and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities divisions. So far, the county has provided around 100 units and expect to install up to 1,000 more air conditioners before July 2023. The State of Oregon also approved funds to purchase air conditioners but haven’t provided reports on whether any have been installed.

But going all in on air conditioners presents a slew of new problems.

- Most air conditioners are only useful up to a temperature of 100° and can generally only bring temperatures down by about 30°. With climate change increasing and minimal efforts to stop it, we’ll likely see more than 35 days of extreme heat annually by 2050. Depending on which forecast model you look at, Portland’s average ‘extreme heat’ temperatures could exceed 105°.

- Air conditioners expel hot air, multiplying the effects of heat islands. They’re directly linked to higher nighttime temperatures, making cooling homes even harder.

- Air conditioners require power. Even the most energy efficient model can raise a household’s energy bill by at least $30 during warm months. Less efficient models will add more than $50. (Those numbers are accurate for early 2022, but are subject to inflation and rate increases.) People with air conditioners can face a decision between cooling their homes or paying other bills.

- The increased power demands put more pressure on our aging power grid, making power outages even more likely during extreme weather. And if the power is out, the only people who will be able to run their air conditioners are the folks who can plop down tens of thousands of dollars on installing solar panels and batteries.

- Air conditioners only help people with housing — and even then, people have to live in the right kind of housing. If, say, a building is in such disrepair that running air conditioners create fire hazards, the building’s owner can ban units. That happened last week at Haworth Terrace in Newberg. Buildings need modern electrical systems to support air conditioners, as well as other safety measures.

City and county governments have one other main strategy to respond to heat waves: opening cooling shelters. Last week, Multnomah County operated four 24-hour cooling shelters within the city of Portland. They provided space for approximately 350 people. There were other cooling spaces offered as well, but until 10 p.m. at the latest, while temperatures remained too warm to cool off buildings at night.

Cooling shelters had space for THREE HUNDRED FIFTY PEOPLE. In a city with more than 5,000 people without housing. In a city where more than 100,000 homes likely still don’t have air conditioners.

The only thing that makes that tiny amount of space worse is that the cooling shelters weren’t fully used, hitting a high of 278 guests. There are many reasons why, including:

- Many people I spoke with (including those without housing) didn’t even know the shelters were open. The same holds true of TriMet’s offer of free rides to shelters.

- Trusting these emergency shelters is hard. Such shelters have done substantial harm in the past, including rapidly changing schedules, promising to provide food and failing to do so, and throwing out personal belongings of people staying in the shelters.

- Trusting the City of Portland, in particular, is hard. The city government sent outreach workers to known camp sites to share information about the shelters. At the same time, they swept camps and forced people to move all of their possessions at least a mile in extreme heat. Sweeps are cruel in the best of weather, let alone in the heat.

- Folks who are immunocompromised face extra dangers in using congregate shelters. Even prior to COVID, the process of getting to a shelter and sharing spaces added difficulties and danger to the process for disabled folks.

Running shelters is getting harder, too: The number of extreme weather situations requiring emergency shelters increases every year. Multnomah County and its partners reported that running shelters from Tuesday to Sunday last week marked the longest run of cooling shelters the county has ever provided. In Oregon, most of the people working in shelters are volunteers, either from emergency response groups like NET or recruited for the specific emergency. But these systems have worked volunteers to the point where people are exhausted and put them in positions they aren’t trained for.

And between pandemics, recessions, and compassion fatigue, people who volunteered to help five years ago are far less likely to be able to volunteer today, because they need help themselves.

What’s the solution?

Perhaps the most frustrating part of all of this is that these problems are all solvable, with a little political or organizing power.

Government-led solutions

Ultimately, local governments should protect and improve the lives of the people within their jurisdiction. There’s plenty of power to implement useful solutions if an official is willing to fight for that solution. So what do we need?

- A decentralized shelter system: Emergency shelters are key to effective emergency response, because providing help is always easier in a centralized location. Creating smaller neighborhood-based shelters could provide that centralization while still making spaces accessible no matter where people need help. These shelters need to be trustworthy, so following the leadership of people who have experienced homelessness and working with organizations who already have the trust of their neighbors could be ways to create a shelter system people can actually use. A decentralized shelter network would also allow shelters some independence in determining when to open, rather than relying on meeting some specific metric.

- Professional staff: Emergency response (including staffing shelters) is not entry-level work. People doing this work frequently need long-term support, not just a little organization and some classes from FEMA. The logical solution is to hire people — a lot of people — to do this work, as well as better preparing community members between immediate needs. There are plenty of ways such a staff could keep busy between emergencies. For instance, they could take over the social safety net tasks that have been forced onto librarians and other front-facing workers.

- Providing housing: The “Housing First” model is the most effective way to respond to homelessness. We have research, examples in action, feedback from people served, and a mountain of other evidence. Our elected officials need to double down on providing housing to people and shutting down arguments about whether people ‘deserve’ housing. They also need to support self-organized efforts to provide safe camp locations and housing.

- Overhauling building codes: Our current building codes set the lowest expectations for new construction. Mandating passive improvements to new constructions and during remodels would be a major improvement. Passive improvements, such as well-controlled shading and natural ventilation, are important even in air-conditioned spaces. They can reduce the energy needed to bring temperatures down by as much as 80 percent.

- Reducing incarceration: Prisons and jails throughout the state take minimal steps to respond to emergency conditions among prisoners. DeWayne Hendrix, the warden of the Federal Correctional Institution in Sheridan, even used June’s high temperatures to punish incarcerated people for a hunger strike, by turning off showers after temperatures reached 90°. The only reform that will protect lives is removing people from a system where emergencies are welcomed as a way to make their lives worse.

- Oversee businesses effectively: Businesses ignore worker safety guidelines because they can afford to do so. Ernest Nursery and Farms received a $4,200 fine for heat wave violations that resulted in the death of Sebastian Francisco-Perez in 2021. That fine is nothing but a fee for doing business.

- Address climate changes: The City of Portland talks about climate change a lot and even just voted on a new ‘Climate Emergency Work Plan’. But there’s minimal urgency at City Hall. Reducing heat islands in the city would make major differences in how bad heat waves get, for instance. If we dream big, though, local governments have power they can use to pressure both industry and national governments to take effective change.

Frankly, I don’t have a lot of hope that any of these solutions will be implemented. Portland’s city government doesn’t work well. Wheeler routinely uses emergency orders to criminalize homelessness. Elected leaders, like Wheeler and Mingus Mapps, are fighting hard against reform proposals that would make the City of Portland functional (along with a variety of business interests). The City of Portland is even removing funding from Friends of Trees, eliminating the largest tree-planting program in the area. Without major changes to city leadership, I can’t imagine a mayor and city council actually working to protect people in a meaningful way.

Having confidence in other levels of government is also difficult. The first debate between candidates for Oregon governor happened Friday, July 29. Betsy Johnson touted Bybee Lakes Hope Center (the former Wapato Jail) as a success and boast about how people are out on the street if they can’t manage addictions — on the same day that people were dying because of the conditions on the street. Two of the three candidates in this race will defer to business interests on most issues, including climate change and homelessness. The third, Tina Kotek, is better in comparison but neither her climate change nor housing plans discuss the issues listed above.

Mutual aid solutions

We’re already relying heavily on mutual aid solutions here in Portland. Wheeler himself has advocated for more mutual aid, although his support is probably more about disinterest in doing his job than anything else.

Personally, I believe in mutual aid’s usefulness for other reasons. Empowering people to respond to the situations we see, rather than waiting around for some sort of official response, will always provide faster care. In emergencies, speed saves lives. On the most basic level, the Red Cross estimates that, in immediate emergencies, 90 percent of the people providing life-saving first aid are not professional responders. Instead, the people who save lives in emergencies are the people who are right there, experiencing those crises. Mutual aid also means that we’re not separating communities into ‘people who need help’ and ‘people who can help.’ Few people actually exist in one category and such divisions tend to result in responses that do more harm than good.

We can’t sit around while we’re hoping that an elected official or two will advocate for meaningful change. We can build out mutual aid networks that make this work more doable. There are a few areas ripe for mutual aid efforts.

- A centralized communication system: During emergencies, I put together running lists of resources, ways to help, and other information. It’s become one of my main mutual aid projects because I see so much information scattered across social media, news sites, government press releases, and other sources. But a shared list is not enough. We need standing communications systems that people can use to request, share, and create resources, as well as ways to collect and share data. It needs to be accessible to everyone, even folks who don’t use social media or have fancy gadgets.

- Home repair and improvement efforts: Hardening a home against climate change requires a lot of work. Regularly cleaning HVAC filters, for instance improves both HVAC functioning and the health of the people using those systems. But it can be a tough task for a lot of people due to health, ability, and other factors. We already have groups like Repair Bloc PDX that are helping folks with their homes. We can build on those successes to help everyone make sure that their home is as safe as possible.

- More shelters and housing: The number of housing mutual aid efforts already in place give me hope. From making sure folks at least have sleeping bags and tents to paying for temporary housing for folks to building homes, people are already doing great work. The more people who get involved, the more mutual aid projects can grow.

- Worker education and organizing: Removing necessary resources, including labor, is the most effective way to convince a company to do anything. If we want everyone to have safe working conditions, including during heat waves, we need people to feel comfortable walking off an unsafe job. That’s a lot of work, because there are no legal protections for employees who walk out or refuse an assignment due to safety. We need comprehensive worker education, financial support for missed work, and ways to hold employers accountable. Unions are already on top of a lot of this work, but unions aren’t everywhere or all-powerful.

- Green spaces: We know that heat wave deaths happen more in heat islands. We can break up at least some heat islands by creating more green spaces. Parks, gardens, and larger efforts make the most change, but just depaving small areas and adding plants to untended spaces helps. Be aware that unofficial green spaces will likely be destroyed and be prepared to start over as needed.

- Your own needs: We each need different things to survive emergencies. The items listed above are things I know about, from my own experience. But I’m sure there are things I’ve left off, so the more that each of us can participate in mutual aid, the more solutions we can offer. Bringing up an issue is a key part of mutual aid and an easy way to get involved if you haven’t done any mutual aid before.

We can’t wait for better emergency response

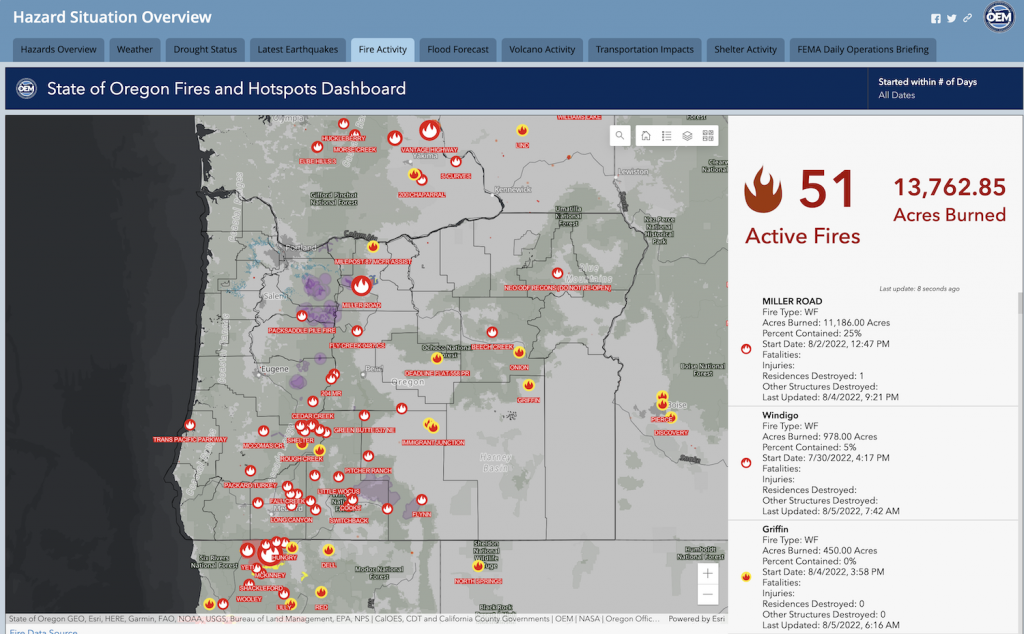

Last week’s heat wave isn’t the last emergency Portland will face this summer. Right now, there are more than 50 wildfires burning within Oregon’s borders and plenty more in adjoining states. Even if no fires start closer to Portland, we’ll be seeing more air quality alerts and we’ll need to support response efforts in nearby communities. We also have a heat advisory for this weekend, with temperatures on Sunday currently predicted to hit 100°.

We need better emergency response systems now. That includes holding local governments accountable for the work they claim to do, as well as building out more mutual aid networks.