If you live in Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington Counties, you have something on your ballot that no one else in the U.S. has — a directly elected regional government in the form of Metro. Metro is also the only directly elected metropolitan planning organization in the U.S.

While knowing our local government is unique can make us feel special, Metro’s purpose makes explaining Portland politics harder. So let’s break down what Metro does, where it came from, and where it could go.

Metro: An overview

Metro’s original purpose was to manage long-term regional planning. That includes both big picture planning, like frameworks around what kind of place the region should be, as well as detailed decisions, like reviewing and expanding the urban growth boundary (more on that later). In order to do that work, Metro is also responsible for maintaining tools and data, as well as compiling research. To manage these sorts of projects, Metro works with the state government, the three counties included in their territory, and 24 cities including Portland.

Since Metro’s creation thirty years ago, the agency has also been handed other responsibilities:

- Managing open spaces, including opening new parks like Newell Creek Canyon in Oregon City and Chehalem Ridge in Gaston

- Operating recreation facilities, including the Oregon Zoo, the Oregon Convention Center, and the Portland Center for the Performing Arts

- Disposing of household trash and other solid waste, including operating landfills and collecting abandoned waste

Metro’s total budget is now over $1.6 billion annually, funded through taxes, revenue from various fees, funding from federal and state agencies, and interest earnings. Currently, around 1,025 people work for Metro.

Currently, Metro is a bit of a catchall for governmental projects that require coordination between multiple local governments. They also pick up the occasional project that a small local government isn’t in a position to take on. The wide variety of work done by the agency makes understanding their position in local governance that much harder.

One of the reasons Metro is able to run those larger projects is because it has a larger tax base than an individual count. It’s not at the level of the state’s tax base, but the more than 1.5 million people living in Metro’s territory makes Metro a fundraising system for the counties. Two recent measures in particular, meant to help with affordable housing and homeless services, have been structured to raise revenue across Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington Counties.

Why does Metro even exist?

Metro is only the most recent in a line of regional planning efforts in the Portland area, dating back to before World War II. Since the 1950s, those efforts have been centralized in some sort of agency. The organization we now know as Metro is 30 years old.

A brief timeline

- 1957 — Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington Counties formed a Metropolitan Planning Commission responsible for doing research and providing a forum for long-range planning in order to use federal funds earmarked for regional planning. This commission built on previous urban planning initiatives in the 1920s and 1940s.

- 1966 — MPC was replaced by the Columbia Region Association of Governments, which took on MPC’s responsibilities, as well as met federal requirements around metropolitan representation. CRAG included Columbia and Clark Counties.

- 1973 — The Oregon State Legislature changed CRAG from a voluntary organization of local governments into a formal regional planning district for Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington Counties. Under the leadership of then-mayor of Portland, Neil Goldschmidt, the district structure was used to redirect funds intended for the canceled Mount Hood Freeway, to fund projects in downtown Portland.

- 1978 — Voters in Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington Counties approve a ballot measure creating a directly elected council to operate the Metropolitan Service District (now known as Metro). Ballot language implied the new council would be weaker than CRAG, but the resulting government proved significantly stronger than expected

- 1992 — Metro voters approved a new charter for Metro, reducing the number of council members and adding an independently elected auditor.

- 2002 — Metro voters amended the charter to centralize power and reduce the number of councilors.

Metro’s charter is relatively unchanged since 2002. The charter sets out territorial boundaries, governance, tax and bond options, and other operational details.

There are pretty routine calls for dissolving Metro and handing its powers either to the State of Oregon, to the counties included in Metro, or to the City of Portland. Just about every article I read in researching this article had at least one suggestion to just get rid of Metro in the comments. Somehow, Metro has stuck around and even grown in power.

A note on Metro and TriMet

Given Metro’s geographical territory and focus on transportation, assuming Metro manages TriMet would make sense. However, TriMet is not under Metro’s administration but is instead operated by the State of Oregon through a municipal corporation. Municipal corporations are, legally speaking, local governing bodies (like cities or counties). Oregon’s governor appoints members to a board of directors for four-year terms. That board is responsible for all decision-making for TriMet, with the support of an executive team to actually do day-to-day work.

However! The Metro Charter says that Metro can take over management of TriMet just with a majority vote of the Metro Council and a consultation with a few other regional officials. The State of Oregon’s statues make the charter clause possible. In Section 7, which covers the assumption of additional functions, the charter states:

(4) Assumption of Functions and Operations of Mass Transit District. Notwithstanding subsection (2) of this section, Metro may at any time assume the duties, functions, powers and operations of a mass transit district by ordinance. Before adoption of this ordinance the Council shall seek the advice of the Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation or its successor. After assuming the functions and operations of a mass transit district, the Council shall establish a mass transit commission of not fewer than seven members and determine its duties in administering mass transit functions for Metro. The members of the governing body of the mass transit district at the time of its assumption by Metro are members of the initial Metro mass transit commission for the remainder of their respective terms of office.

Don’t expect Metro to pick up responsibility for TriMet tomorrow. That change would likely require a lot more than a vote to actually implement. But it is on the table and could be a way to combat TriMet’s perceived lack of transparency and responsiveness to local residents.

Metro’s impact on housing

Metro is a major influence on housing availability across the Portland metro area and surrounding counties. Recent ballot measures have provided Metro with money to improve access to affordable housing as well as homelessness support services. But that’s only one way the agency impacts housing. Their responsibility for the urban growth boundary may be even more direct, depending on which researchers you believe.

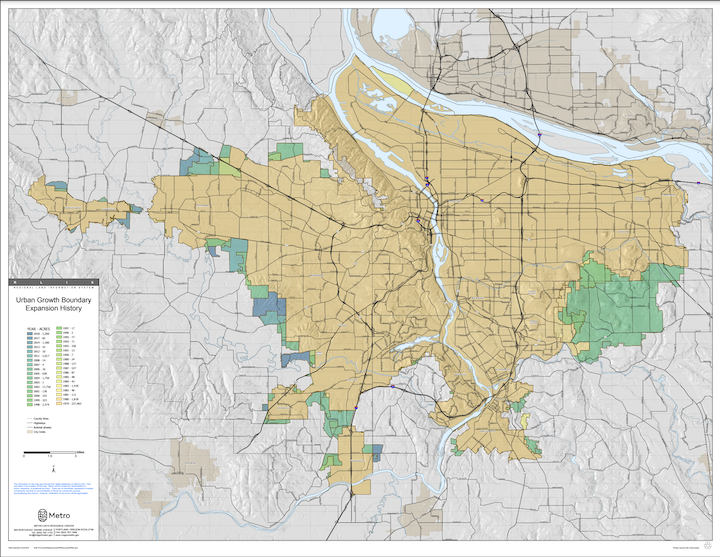

The UBG is intended to guarantee that there is a 20-year supply of developable land in the area, while preserving green spaces and agricultural land. Metro is responsible for reviewing and setting the UBG every six years for Portland and other cities in their territory. That means Metro decides how much land is actually available for building housing. In 2018, the most recent review, the Metro Council moved 2,181 acres from outside the UBG to inside, with the expectation that at least 9,200 homes will be built on that land. The next review will take place in 2024 and will likely be just as controversial as every other UGB review has been.

Exactly how the UGB impacts housing development and housing prices is complicated. One of the goals for the UGB when it was created in 1979 was encouraging high density construction and housing infill. By 1998, the UGB was seen as a driver of Portland’s on-going affordable housing crisis. Portland’s housing crisis arguably started in 1995, when the region first saw average housing prices above the national average. Housing prices dipped during the Great Recession, but so did construction of new housing. Portland is missing somewhere around 50,000 housing units due to a lack of construction at that time.

In 2000, researchers Justin Phillips and Eban Goodstein demonstrated statistically that the UGB pushes housing prices up, but by less than $10,000 per house. Furthermore, an area’s inclusion is the UBG doesn’t mean that housing will be built on that land. Between 1998 and 2014, 93% of new housing was built within the original 1979 UBG, effectively ignoring any newly added land. That’s one of the reasons Metro keeps new additions to the UBG to a minimum. Their limits are a demonstration of substantial political power, especially when you read through old articles and op-eds full of property owners pushing for changes in one direction or another.

Metro’s long-term regional planning efforts also impact the availability of housing in other ways. The agency is heavily involved in planning and funding transportation projects, such as the $36 million they’re kicking in for the planned replacement for the Interstate-5 bridge over the Columbia River.

Metro also directly supports the construction of affordable housing, by acquiring land and offering direct funding to developers. The Transit-Oriented Development program focuses on building affordable housing near transit. Through that program, Metro has helped build 2,016 affordable housing units near transit plus another 3,416 market rate housing units, since 2000. The funding package passed in 2020 increased their abilities in that area as well. Funds from the tax have been available to local governments and non-profits since June 2021. In the first six months of funding, those organizations have helped about 500 people into permanent housing, created more than 450 new shelter beds, and prevented 1,400 evictions. The large amount of money raised has made Metro a target, though.

People for Portland is pushing to add a ballot measure to the general election that would redirect funding from the 2020 measure to emergency shelters. Of course, moving money away from long-term solutions to emergency shelters guarantees that people will be in those emergency shelters for years to come. And by taking money away from eviction prevention, People for Portland’s measure might even increase the number of people without housing. People for Portland’s flawed plan may not make it to the ballot — so far Metro’s legal team has rejected proposed ballot measure language twice. But People for Portland has gone ahead and started fundraising for signature-gathering in anticipation of moving their ballot measure forward. The dark money group has also targeted Lynn Peterson, the Metro Council President, in the current election.

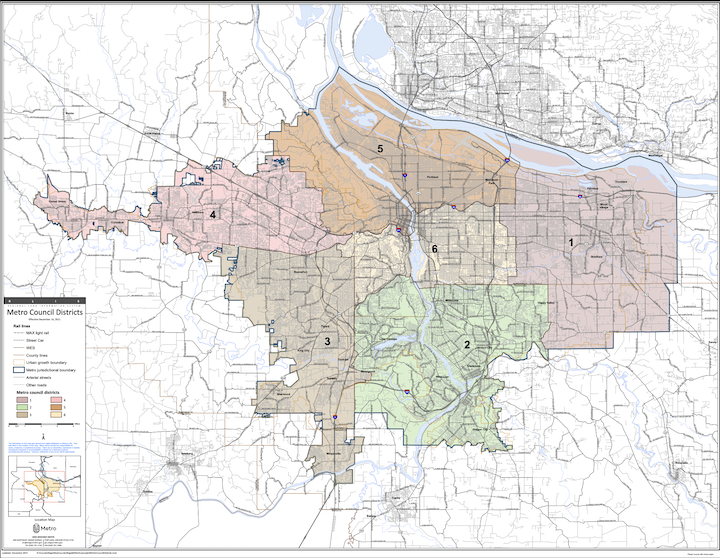

Metro’s leadership

Metro is lead by an elected council of six members, plus a council president. Voters also elect an independent auditor to provide oversight for Metro. None of Metro’s elected positions are partisan. All of Metro’s elected officials serve four-year terms. Both the council president and the auditor are elected by all voters in the region. The rest of the council is elected by district, with half of the council up for election in each even year. This year is unusual because there are actually four council seats on the ballot, rather than the usual three. Duncan Hwang took over the seat for District 6 in January, after Bob Stacey resigned for health reasons. But Hwang’s appointment is only through the end of 2022; the election will decide who will hold the seat throughout the remainder of Stacey’s term. The seat will be on the 2024 ballot, for a regular four-year term.

Each councilor represents around 275,000 district residents, as of the 2020 census and the 2021 Metro redistricting process. Councilors’ salaries are intended to be a third of a full-time income. As a result, councilors are typically retired or work a full-time job in addition to their work at Metro, which routinely reaches full-time levels. In addition to presenting a major workload, those outside jobs can present problems. Currently, Hwang and Juan Carlos González (the councilor for District 4) both work for non-profits that receive funding from Metro. While both councilors have noted that they are fully complying with state ethics laws and avoiding situations that could present a conflict of interest, there’s a big potential for problems.

The current Metro Council

- Lynn Peterson, Council President — Peterson has been president of the Metro Council since the beginning of 2019. She’s currently running for reelection. Peterson has held a variety of other elected offices, including chair of Clackamas County. She’s also worked in transportation and land use, both as a consultant and in governmental positions.

- Shirley Craddick, District 1 — Craddick has been on the council since the beginning of 2011. While Craddick’s seat is on the ballot this year, she is not running due to term limits. Craddick is retired from her work as a health research and formerly was on the Gresham City Council.

- Christine Lewis, District 2 — Lewis joined the council in January 2019. She is running for reelection on the May ballot. Prior to running for election, Lewis was the legislative director for the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries.

- Gerritt Rosenthal, District 3 — Rosenthal took office in January 2021. His seat will be up for election during the 2024 election cycle. Rosenthal is also an environmental planning consultant.

- Juan Carlos González, District 4 — González has been on the council since the beginning of 2019. He’s running for reelection on the May ballot. González is also the director of development and communications for the Centro Cultural de Washington County.

- Mary Nolan, District 5 — Nolan joined the council in January 2021. Their seat will be on the ballot during the 2024 election cycle. Prior to their time at Metro, Nolan was the majority leader in the Oregon House of Representatives and executive director of Planned Parenthood Advocates of Oregon.

- Duncan Hwang, District 6 — Hwang was appointed to the council in January 2022. He’s running to complete the current term for his seat, which will also be up for election during the 2024 election cycle. Hwang is also the interim co-director at APANO.

- Brian Evans, Auditor — Evans took office in January 2015, giving him a longer tenure at Metro than any council member except for Craddick. He’s running unopposed for reelection on the May ballot. Prior to his election, Evans was a principal management auditor at Metro.

Metro elections don’t attract the attention of state elections or even city elections. While there are six Metro positions on the ballot due back next week, there are just 12 candidates running in those six races. In comparison, the City of Portland has just three offices on the ballot with more than 20 candidates running.

Evans is unopposed in his reelection run. Ashton Simpson, who is running to replace Craddick as the councilor for District 1, is also unopposed. We’ll likely see incumbents retain their seats in the remaining Metro races.