Wrongful death lawsuit filed against the City of Portland

Portland Police Officer Curtis Brown shot and killed Michael Ray Townsend on June 24, 2021 after Townsend called 911 for mental health help. In September, a grand jury chose to not indict Brown. Townsend’s death is yet another example of the violence the Portland Police Bureau uses against Portland residents, particularly those experiencing mental health crises, that lead to the U.S. Department of Justice’s consent decree against the city.

Townsend’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the City of Portland on Monday, suggesting that the city should have sent mental health professionals to help Townsend through programs such as the Multnomah County Mental Health Call Center or to the Tri-County 911 Service Coordination Program. Townsend’s medical records also show that he attempted to get mental health support at least 14 times between 2015 and 2021, which all presented points where his death could have been prevented.

The family is not seeking financial compensation, but rather a court order that the City of Portland move to send mental health professionals in response to calls like Townsend’s.

New goals for reducing wood smoke

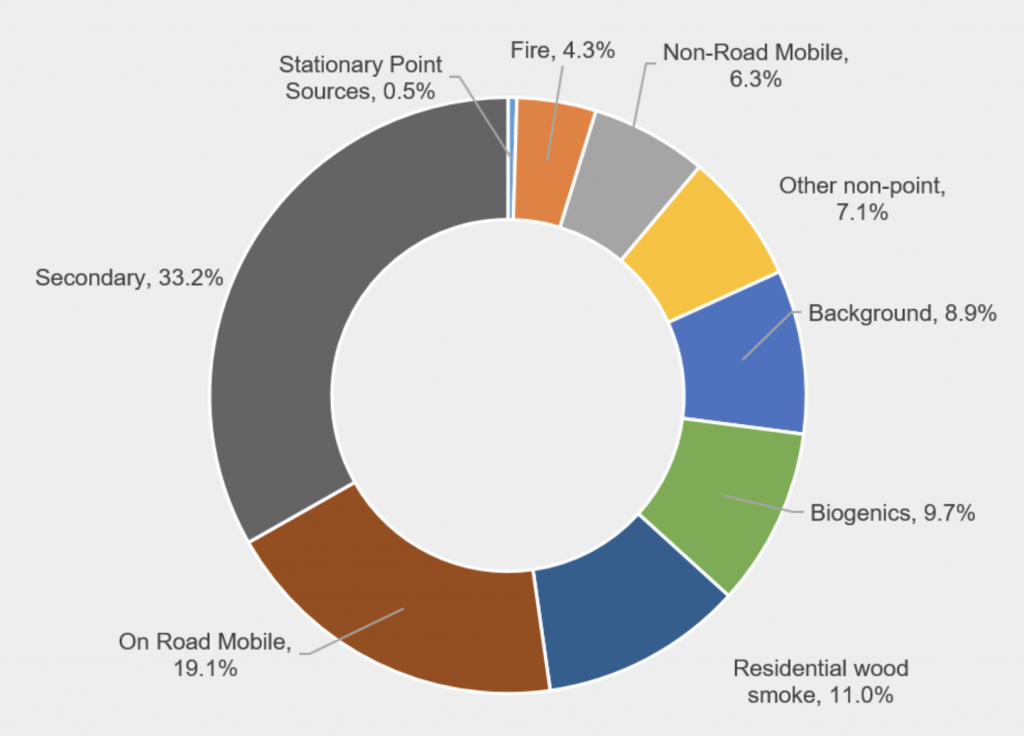

Multnomah County has the dirtiest air in Oregon (which is not necessarily a surprise because Multnomah County is home to almost 20% of the total population of the state). While there are several contributing factors, wood smoke is a key source of pollution. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality estimates Multnomah County residents burn more than 80,000 tons of wood each year for heat, reducing particulate matter into the air. That’s on top of the growing impact of wildfires each summer.

The Multnomah County Board of Commissioners set new goals last week to reduce wood smoke, aligning goals with international benchmarks rather than U.S. federal goals. They’re also considering extending the winter burn ban program passed in 2018 to year-round during tomorrow’s board meeting. The ban goes into affect on Poor Air Quality Days. It was in affect for 24 hours last week. Enforcement of the ban relies on complaints, a system that has been shown to impact people of color significantly more in other Portland-area enforcement attempts. Winter burn bans do not include those whose only source of heat is wood burning, but it does cover anyone with a furnace or another heating system, even if that system is disconnected from its fuel source.

Reducing wood smoke won’t just reduce air pollution. Particulates from burning wood have been linked to major health impacts, including reduced lung function. Communities more likely to experience poverty and therefore rely on wood burning as a source of heat are hit especially hard. Those communities, which include people of color, are also more likely to catch COVID-19 and face reduced lung function as a result of the illness, as well. However, Multnomah County’s new policy doesn’t provide community members who rely on wood burning for winter heat with an alternative. A proposed clean air initiative from the City of Portland also fails to address replacing wood burning as a heat source. There are a few state-level programs in place, including cash incentives for replacement, but those programs primarily target home owners.

Private casino ban ruled constitutional

Travis Boersma, the co-founder of Dutch Bros Coffee, has been pushing for state approval of a new gambling facility in southern Oregon. The gaming center would be part of the Flying Lark racing center at the Grants Pass Downs racetrack. Oregon has long prohibited casinos outside of tribal lands and the Oregon Department of Justice ruled on Friday that Boersma’s facility would violate the state constitution. The ruling doesn’t necessarily mean that Boersma will give up on the project: the Oregon Racing Commission still technically has the power to approve the new facility (although a lawsuit would likely result). Boersma can also continue to pursue the issue in court. Boersma might also seek out a tribal partner for the project, although his efforts so far probably haven’t won him any friends in the local tribes. The secretary of state’s office is also auditing the ORC’s regulatory and oversight structure in response to concerns from tribal governments.

Several tribes have lobbied against the project throughout its development, which would likely compete with tribal casinos. Tribal casinos are one of the main sources of revenue for funding health, education, and other vital services on tribal lands. John McCafferty, the president of the Umpqua Indian Development Corporation, estimates that the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe Indians would face an initial loss of casino revenue of $20 million, which would in turn require layoffs across the tribe’s operations.

One concerning aspect of Boersma’s efforts surrounding the Flying Lark facility is his threat to lay off 225 employees if the Oregon Racing Commission does not grant approval for adding gambling to the site. Flying Lark’s racing business does not require violating the state constitution in order to function. The average income in Josephine County, where the Flying Lark is located, is $45,616. To pay 225 employees that amount for a year without any of the income that the Flying Lark likely produces, Boersma would need $10.2 million or just 0.045% of Boersma’s net worth of $2.3 billion.

A quick note about PDX.Vote mechanics

If you’re interested in submitting something to the site, I did a long-ish Twitter thread yesterday that includes what I’m looking for, pay rates, and even a couple of article topics I want to commission pieces about.

I’m paying for these contributions out of my personal funds. If you find the coverage from this site useful, please consider supporting it. And thank you to the five people who have already signed up to support PDX.Vote on a recurring basis — y’all are amazing and I appreciate you.

1 comment

Comments are closed.