I’ve done a lot of research into Portland’s local news ecosystem, as well as the national trends that have shaped it, as part of creating this site. Given the substantial impact of local reporting on local elections, I’ve put together this overview on some of the different facets of Portland’s media. I’ve divided this article into two halves: Part One focuses on who reads and pays for local news, while Part Two covers who profits from locals news and determines what is covered.

What is Portland media?

Determining the number of Portland news sources is harder than just counting newspapers, magazines, television stations, websites, and radio stations. Do you count publications that include news that impacts Portland even though they aren’t produced here — like Salem publications that cover the state legislature — or blogs that may have useful information but are produced by companies that primarily do business in other industries? You also have to decide where Portland ends: Is unincorporated Multnomah county part of Portland? What about Vancouver, Washington?

For the purposes of this article, I’ve taken an expansive view of local media, because political coverage pops up all over. The Canby Herald may have information about candidates running for Clackamas County commissioner, a position responsible for a chunk of Portland. I’ve included publications covering legislative news from Salem, but not publications focused on Salem’s news. Similarly, I’ve included news from Oregon reservations, but not publications focused on the towns around those reservations. However, I have not included publications focused on legislative news from Washington, D.C. I’ve included small publications, like blogs and neighborhood newspapers, but not out-of-state publications that happen to have regular contributors in Portland.

Here is a list of the publications on my radar:

Who consumes what news?

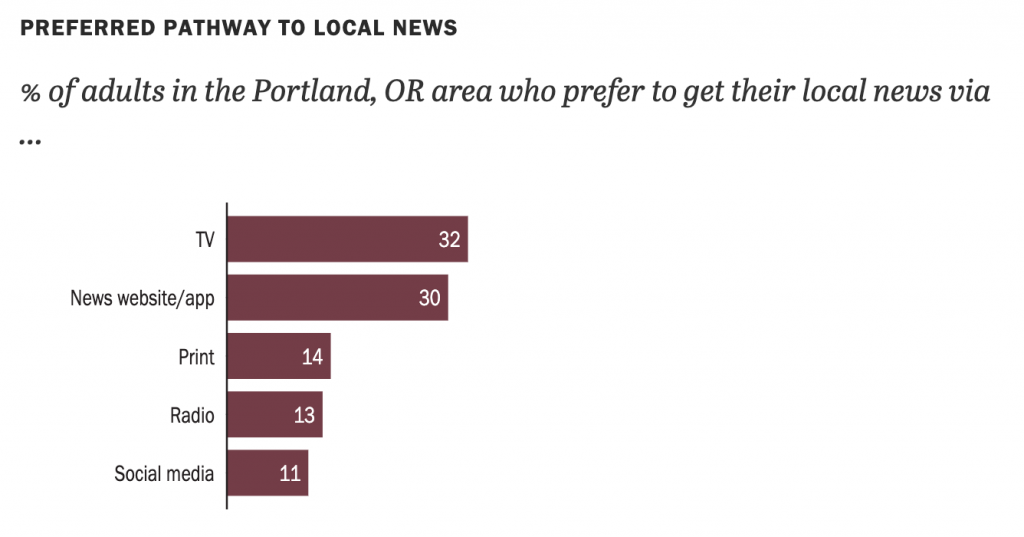

Most of the news sources in Portland have an online presence, even if they primarily produce for print or broadcast. Most adults in the US get at least some of their news online, so I’ve focused on the online presences of all the news sources I’ve reviewed. However, it’s important to note that many people tune into a television broadcast or open a newspaper to get at least part of their news. In 2020, local television news companies generated more revenue than in 2019 and saw viewership go up. Part of that increase is cyclical, tied to presidential elections, but COVID-19 also drove increased viewership. As of 2019, 32% of Portlanders preferred to get their news from television according to a Pew survey.

In contrast, print newspapers have continued to decline. Some newspapers have seen increasing digital circulation, but there’s no good data on readership numbers for most newspaper websites. AAM estimates that total newspaper circulation in the US fell 6% in 2020 (including digital circulation), with a loss of close to 20% of print circulation. And 2020 was likely the best year for US newspaper circulation in years. COVID likely accelerated the decline of print newspapers: The Portland Mercury ended print production (potentially temporarily), like many other newspapers across the US. Only 14% of Portlanders reported getting their news primarily from newspapers in 2019. I expect that percentage has dropped further in the last two years as newspapers have shifted away from dead-tree formats.

Legacy media websites are only part of the online news picture. Online-first sources, such as podcasts, continue to grow. News publishers, such The Oregonian and OPB, have created local podcasts. So have have institutions like the Oregon Historical Society. There are also many independent podcasts covering specific facets of Portland news, such as Your Neighborhood Black Friends and Portland from the Left. Around 30% of Portlanders reported preferring websites and apps for getting their news in 2019. Blogs and email newsletters also have a place in the Portland news ecosystem. The Oregon Way, for instance, is a nonpartisan political newsletter that has expanded to include a podcast and opinion pieces from Oregon notables. Of course, there’s more turnover among independent news sources: A few years ago, I might have turned to The Racist Sandwich or BlueOregon for certain types of news, but Racist Sandwich is on hiatus and Blue Oregon hasn’t updated in a year.

Many Portlanders see social media platforms as a key source of news: During the George Floyd uprising in 2020, independent journalists on Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and other platforms provided key coverage. Just over half of adults in the US report getting news from social media sites in 2020 and 11% of Portlanders reported using social media as their main source of news in 2019.

Radio captured 13% of Portland news consumers in 2019. Our local radio scene is particularly diverse, at least in terms of the number of languages news is offered in. There are multiple Spanish-language stations, as well as stations broadcasting in Slavic and Asian languages. In contrast, there are only a handful of other news sources in Spanish spread out across different media. Finding Portland news in languages other than English and Spanish is difficult and many communities seem to rely on informal news-sharing and translation systems.

Who pays for news?

The most important demographic factor in Portland news is which news consumers are willing to financially support local news providers. As of 2019, only 14% of adults in the US reported paying for local news. Typically, the folks paying for news are older, have college degrees, and are white. Those demographics suggest that the folks paying for news are the folks most likely to have both discretionary income and an expectation that they can successfully participate in local politics. We saw an outpouring of financial support for local publications in 2020 that may not have come from that demographic. However, we don’t have numbers on the funds raised to keep publications like the Portland Mercury and Willamette Week afloat when their print editions and events were canceled.

If you were to pay for a subscription to every news source in my list that offers a subscription, you could expect to pay about $2,000 per year. Your money would go to print and online subscriptions. You’d also get a cable television subscription if you want to watch public access shows on television rather than online.

There are several news sources that accept donations but do not require readers or listeners to pony up in exchange for access: OPB and KBOO come to mind, but publications like the Portland Mercury have started asking for financial support over the past two years. It’s worth noting that non-profit and for-profit organizations alike ask for financial support.

Individual giving to media has gone up quite a bit in the past several years, especially after the 2016 presidential election. Pew offers some interesting numbers on public broadcasters: “In 2014, for example, just 3% of nonpublic funding for the PBS NewsHour came from individuals. By 2020, the share had climbed to 24%. Over the same period, contributions from corporations fell from 41% to 18%, according to information provided by PBS NewsHour. At public radio stations, meanwhile, individual contributions rose from $261 million to $430 million between 2008 and 2019, while underwriting revenue has risen far less…”

News consumers don’t provide enough funds to cover operation costs for either large publishers and independent producers. Some non-profit news sources are able to use grants and institutional funding to cover their expenses. For-profit organizations routinely rely on advertising, as well as events, custom publishing, and other revenue streams that are related in some way to their news coverage. Companies with owners and investors expecting high returns are more likely to establish additional revenue streams.

Advertising is a key source of revenue for large publishers in particular. Digital advertising’s growth makes estimating advertising revenues from journalism difficult. Most analysis covers all digital advertising, rather than breaking it down by types of site. Someone’s personal site about their puppy that runs Google Ads shows up in the same analysis as a daily newspaper that sells space directly to advertisers. As of 2019, digital advertising raised more revenue than non-digital advertising. According to eMarketer, “In 2020, according to eMarketer estimates, digital advertising grew to $152 billion, an increase from $132 billion in 2019 and $111 billion in 2018. It was estimated to comprise 63% of all advertising revenue, up from 55% in 2019 and 49% in 2018.” There’s a growing question, however, of whether advertising can grow enough to support the range of news sites launching online.

Independent producers often cover costs out of their own pockets, relying on income sources outside of journalism to meet expenses. PDX.Vote is in this position. While I hope readers will find the site valuable enough to provide financial support, I’m funding this project personally. I’m reluctant to use either advertising or pay walls due to concerns touched on below. While we’re early days yet, I have looked at the finances of other local independent media as a starting point. One interview particularly stood out: I talked to Audrey Eschright, the publisher of RE: Portland, a site that covered the George Floyd uprising starting in June 2020. Eschright worked with freelancers to track articles and social media posts during each night’s protests, offering a variety of angles about each evening’s events rather than a raw feed. Eschright paid contributors a day rate, working with a rotating group of freelancers to cover each night without forcing anyone to stare at descriptions of police brutality to the point of trauma. Each night could range from four to eight hours of work. Eschright noted that the protest blog did not earn any direct or indirect income: “I didn’t want to detract from efforts to support the reporters who were on the ground, so I decided to hold off on asking for donations over social media. Getting the information out to people felt important enough to take the risk, but I won’t be able to do a project like this again without more dedicated financial support.”

News is increasingly seen as a public utility. To that end, there are legislative efforts to ensure local journalism is better funded. The Local Journalism Sustainability Act was initially introduced during the 2020 congressional session and was reintroduced this year. If passed, it would create three tax credits intended to encourage local media (defined as a publication where a majority of readers live within a 200-mile radius):

- a tax credit for consumers of up to $250 per year for a subscription to a local newspaper,

- a tax credit for local media publishers worth up to $50,000 per year to hire and pay journalists, and

- a tax credit for businesses advertising with local media worth up to $5,000 per year.

Whether the Local Journalism Sustainability Act would really help local news publishers is up for debate. The bill focuses on helping existing publications, particularly those that rely on subscriptions for funding. That means maintaining a status quo: white editorial staff, often male, lead most of those news organizations. Many news sources led by people from other marginalized backgrounds are free to readers, relying on a variety of community support to operate. At best, the Local Journalism Sustainability Act is a short-term solution that ignores root problems. Furthermore, the act would support print media over other formats. We’re already at a point where print media is demonstrably reaching fewer readers than either online platforms or broadcast media, so that support isn’t so helpful.

The conglomeration of news media makes the situation worse: Hedge funds and investment groups own loads of newspapers and broadcast stations. They demand profits from their properties that would otherwise fund investigative journalism or expanding coverage. Half of daily newspaper circulation comes from newspapers owned by hedge funds. For those searching for a legislative solution, antitrust regulation is one option. For the last forty years or so, antitrust regulators have largely ignored media. However, using antitrust regulations runs the same risks as other legislative options already on the table. Regulators would probably reinforce an inequitable status quo and support publications that aren’t sharing news in places news consumers actually are.

Who pays for a lack of news?

While accessing news can be expensive, the consequences of not having local news sources available can cost even more. Establishing a direct link between a lack of news sources and specific impacts is difficult. But researchers have demonstrated a variety of connections and correlations to the closure of local news sources. Both governance and accountability become much more expensive.

A 2019 study found that the cost of local government to taxpayers goes up significantly. Taxes paid by residents increase on the county level. Local officials’ wages increase. The number of government employees per capita increases. Government deficits increase. Bond issues and other municipal borrowing costs also increase. Without a news publisher capable of investigative journalism around, local governments become less efficient and less able to access outside funding if needed. Federal funding also decreases, according to a 2008 paper: federal spending drops in areas without local political reporting due to less local accountability for federal representatives. As the paper’s authors, James Snyder and David Strömberg, note, “Voters living in areas with less coverage of their U.S. House representative are less likely to recall their representative’s name, and less able to describe and rate them. Congressmen who are less covered by the local press work less for their constituencies: they are less likely to stand witness before congressional hearings, to serve on constituency-oriented committees (perhaps), and to vote against the party line.” Voters can’t hold elected officials accountable without journalists working on their behalf.

Other forms of accountability also suffer without local reporting. A 2018 paper examined plant-level toxic emissions in the US alongside the location and content of newspapers. They found plants operating in an area with a large number of locally managed newspapers produced lower toxic emissions. Whether a plant makes it into the local newspaper depends directly on whether that newspaper is headquartered nearby. When a newspaper’s owners live and work outside of the paper’s coverage area, that paper is less likely to cover environmental issues. Phil Luciano, a columnist for the Journal Star in Peoria, Illinois, spoke to PEN America about his experiences attempting to cover local news. He received a tip about Caterpillar, which is based in Peoria, but couldn’t follow up due to a lack of resources. Luciano said dead-end tips are “endemic to slashed newsrooms every day. Newspapers once had beat reporters who didn’t just show newspaper coverage, the plant reduces emissions by an average of 29 percent compared with plants that do not receive coverage.”

Requiring a subscription to access certain news stories may also have chilling effects. I’m all for supporting newspapers and other news media through subscriptions. But their reliance on subscriptions means that important information winds up behind paywalls. Perhaps one of the most infuriating examples I’ve found is that at least two local publications placed content about the 2020 heat waves behind their paywall. Potentially life-saving information was available only to those who paid for access. Many news sites dropped their paywalls on COVID-19 coverage in early 2020, but those paywalls have slowly crept back up again. One of the reasons I started PDX.Vote is that limiting access to political coverage endangers our ability to hold elected officials accountable for their actions.

While all news coverage has some inherent bias from the people producing it, news conglomerates are able to push their bias harder than media companies that have one or two news properties. The Sinclair Broadcast Group, for instance, is the largest owner of television stations in the US and reportedly provides news to 40 percent of households in the country. In Portland, the company owns two television stations. Sinclair routinely creates national news packages that show on all of its channels, often with far-right slants. Local anchors are required to read these packages. In 2018, anonymous news staff working at Sinclair affiliates attempted to push back and provided a joint op-ed to Vox: “Our anchors privately said they felt like corporate mouthpieces, especially when they found out no edits of the script were permitted. Yet bosses made it clear that reading the message wasn’t a suggestion but an order from above.” David Smith, the chairman of the Sinclair Broadcast Group, has made his agenda clear on numerous occasions. He even told the Trump administration that “We are here to deliver your message.”

Communities that are already marginalized see outsized impacts from a lack of local independent coverage. The number of Indigenous newspapers shrank alongside other independent media sources. In 1998, there were 700 Indigenous media sources in the US and only 200 in 2018. Of those that remain, a majority are operated by tribal governments. Indigenous journalists struggle to hold tribal governments accountable for their actions as a result. One concerning incident took place here in Oregon in 2014: The Confederated Tribes of Grande Ronde’s tribal council chose to remove more than 80 members of the tribe from tribal rolls. When Smoke Signals, the newspaper owned by the Confederated Tribes of Grande Ronde, attempted to write about it, reporters were told not to cover aspects of the decision. Dean Rhodes, the editor of Smoke Signals, said that he likely would have been fired if the newspaper had published any story with a hint of sympathy for the tribal members who were disenrolled. The decision was later reversed.

These journalistic failures endanger everyone living in areas without locally operated media sources. Having few independent news sources drives up the cost of living in an area far beyond the cost of a few newspaper subscriptions.

Continue reading about the Portland news ecosystem in Part Two.

4 comments

Comments are closed.